-- A Room With A View, E. M. Forster

Till we have faces

Sunday, April 21, 2013

Beware of muddle.

'"Take an old man's word; there's nothing worse than a muddle in all the world. It is easy to face Death and Fate, and the things that sound so dreadful. It is on my muddles that I look back with horror -- on the things that I might have avoided. We can help one another but little. I used to think I could teach young people the whole of life, but I know better now, and all my teaching of George has come down to this: beware of muddle. Do you remember in that church, when you pretended to be annoyed with me and weren't? Do you remember before, when you refused the room with the view? Those were muddles -- little, but ominous -- and I am fearing that you are in one now." She was silent. "Don't trust me, Miss Honeychurch. Though life is very glorious, it is difficult." She was still silent. "'Life,' wrote a friend of mine, 'is a public performance on the violin, in which you must learn the instrument as you go along.' I think he puts it well. Man has to pick up the use of his functions as he goes along -- especially the function of Love."'

Sunday, April 7, 2013

The yellow wallpaper

http://www.library.csi.cuny.edu/dept/history/lavender/yellowwallpaper.pdf

Many and many a reader has asked that. When the story first came out, in the New England Magazine about 1891, a Boston physician made protest in The Transcript. Such a story ought not to be written, he said; it was enough to drive anyone mad to read it.

Another physician, in Kansas I think, wrote to say that it was the best description of incipient insanity he had ever seen, and -- begging my pardon -- had I been there?

Now the story of the story is this:

For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia -- and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country. This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to "live as domestic a life as far as possible," to "have but two hours' intellectual life a day," and "never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again" as long as I lived. This was in 1887.

I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.

Then, using the remnants of intelligence that remained, and helped by a wise friend, I cast the noted specialist's advice to the winds and went to work again -- work, the normal life of every human being; work, in which is joy and growth and service, without which one is a pauper and a parasite -- ultimately recovering some measure of power.

Being naturally moved to rejoicing by this narrow escape, I wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, with its embellishments and additions, to carry out the ideal (I never had hallucinations or objections to my mural decorations) and sent a copy to the physician who so nearly drove me mad. He never acknowledged it.

The little book is valued by alienists and as a good specimen of one kind of literature. It has, to my knowledge, saved one woman from a similar fate -- so terrifying her family that they let her out into normal activity and she recovered.

But the best result is this. Many years later I was told that the great specialist had admitted to friends of his that he had altered his treatment of neurasthenia since reading The Yellow Wallpaper.

It was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy, and it worked.

---

And that, ladies and gentlemen, was Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her wisdom. To have but two hours' intellectual life a day? How is that called living?

It is a great fear that a child in my care may one day be put in the same position as the author had been through the fault of the great specialist in the sureness of his profession. A teacher is not a doctor and does not have the doctor's capacity for such great harm, but the potential for well-meaning damage remains.

Yet, behold, the power of a widely-read story to change the path of things as almighty as self-conception and medical practice. It has been done and it can be done again. The human race hasn't finished with narratives yet.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman, "Why I Wrote The Yellow Wallpaper" (1913)

This article originally appeared in the October 1913 issue of The Forerunner.

Many and many a reader has asked that. When the story first came out, in the New England Magazine about 1891, a Boston physician made protest in The Transcript. Such a story ought not to be written, he said; it was enough to drive anyone mad to read it.

Another physician, in Kansas I think, wrote to say that it was the best description of incipient insanity he had ever seen, and -- begging my pardon -- had I been there?

Now the story of the story is this:

For many years I suffered from a severe and continuous nervous breakdown tending to melancholia -- and beyond. During about the third year of this trouble I went, in devout faith and some faint stir of hope, to a noted specialist in nervous diseases, the best known in the country. This wise man put me to bed and applied the rest cure, to which a still-good physique responded so promptly that he concluded there was nothing much the matter with me, and sent me home with solemn advice to "live as domestic a life as far as possible," to "have but two hours' intellectual life a day," and "never to touch pen, brush, or pencil again" as long as I lived. This was in 1887.

I went home and obeyed those directions for some three months, and came so near the borderline of utter mental ruin that I could see over.

Then, using the remnants of intelligence that remained, and helped by a wise friend, I cast the noted specialist's advice to the winds and went to work again -- work, the normal life of every human being; work, in which is joy and growth and service, without which one is a pauper and a parasite -- ultimately recovering some measure of power.

Being naturally moved to rejoicing by this narrow escape, I wrote The Yellow Wallpaper, with its embellishments and additions, to carry out the ideal (I never had hallucinations or objections to my mural decorations) and sent a copy to the physician who so nearly drove me mad. He never acknowledged it.

The little book is valued by alienists and as a good specimen of one kind of literature. It has, to my knowledge, saved one woman from a similar fate -- so terrifying her family that they let her out into normal activity and she recovered.

But the best result is this. Many years later I was told that the great specialist had admitted to friends of his that he had altered his treatment of neurasthenia since reading The Yellow Wallpaper.

It was not intended to drive people crazy, but to save people from being driven crazy, and it worked.

---

And that, ladies and gentlemen, was Charlotte Perkins Gilman and her wisdom. To have but two hours' intellectual life a day? How is that called living?

It is a great fear that a child in my care may one day be put in the same position as the author had been through the fault of the great specialist in the sureness of his profession. A teacher is not a doctor and does not have the doctor's capacity for such great harm, but the potential for well-meaning damage remains.

Yet, behold, the power of a widely-read story to change the path of things as almighty as self-conception and medical practice. It has been done and it can be done again. The human race hasn't finished with narratives yet.

Sunday, March 31, 2013

Aubade

Aubade

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what's really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse -

The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused - nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast, moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear - no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anasthetic from which none come round.

And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small, unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can't escape,

Yet can't accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

This is an unfortunate and very true diagnosis of my desire to be useful, and especially of my desire to see young people at their best (which can be magnificent, despite the utter depths of evil that can be their worst). Perhaps it drives not just me but everyone. Larkin has put it into words far better than I could ever have.

No newspaper or government-approved message, no numbers or figures, can acknowledge this darkness behind our copious consumption, our economic creed, our need for forward momentum. An oath on anaesthetic and opiates! We might make light of it, but what light we can make only casts the longer shadow.

I work all day, and get half-drunk at night.

Waking at four to soundless dark, I stare.

In time the curtain-edges will grow light.

Till then I see what's really always there:

Unresting death, a whole day nearer now,

Making all thought impossible but how

And where and when I shall myself die.

Arid interrogation: yet the dread

Of dying, and being dead,

Flashes afresh to hold and horrify.

The mind blanks at the glare. Not in remorse -

The good not done, the love not given, time

Torn off unused - nor wretchedly because

An only life can take so long to climb

Clear of its wrong beginnings, and may never;

But at the total emptiness for ever,

The sure extinction that we travel to

And shall be lost in always. Not to be here,

Not to be anywhere,

And soon; nothing more terrible, nothing more true.

This is a special way of being afraid

No trick dispels. Religion used to try,

That vast, moth-eaten musical brocade

Created to pretend we never die,

And specious stuff that says No rational being

Can fear a thing it will not feel, not seeing

That this is what we fear - no sight, no sound,

No touch or taste or smell, nothing to think with,

Nothing to love or link with,

The anasthetic from which none come round.

And so it stays just on the edge of vision,

A small, unfocused blur, a standing chill

That slows each impulse down to indecision.

Most things may never happen: this one will,

And realisation of it rages out

In furnace-fear when we are caught without

People or drink. Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

Slowly light strengthens, and the room takes shape.

It stands plain as a wardrobe, what we know,

Have always known, know that we can't escape,

Yet can't accept. One side will have to go.

Meanwhile telephones crouch, getting ready to ring

In locked-up offices, and all the uncaring

Intricate rented world begins to rouse.

The sky is white as clay, with no sun.

Work has to be done.

Postmen like doctors go from house to house.

- Philip Larkin

This is an unfortunate and very true diagnosis of my desire to be useful, and especially of my desire to see young people at their best (which can be magnificent, despite the utter depths of evil that can be their worst). Perhaps it drives not just me but everyone. Larkin has put it into words far better than I could ever have.

No newspaper or government-approved message, no numbers or figures, can acknowledge this darkness behind our copious consumption, our economic creed, our need for forward momentum. An oath on anaesthetic and opiates! We might make light of it, but what light we can make only casts the longer shadow.

Thursday, March 21, 2013

Arcana VIII: Strength

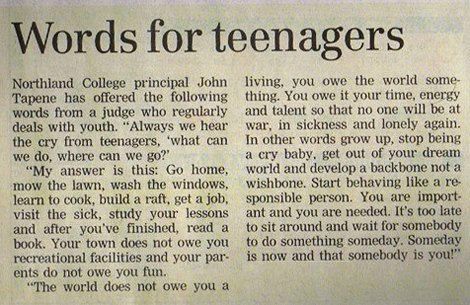

Words condescending but wise. To be fair to the writer of this thing, I too might feel tempted to be condescending if someone came to me whining about having 'nothing to do'. This is the fallacy of individualism: a sense of entitlement and ennui, a guzzling sense of the world failing to succor a vacuous and bloated 'I' when all one really needs to do is to produce worthily -- and grow strong. If you're feeling helpless, help someone. Aung San Syuu Kyi. Quod erat demonstrandum.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/17/fashion/the-family-stories-that-bind-us-this-life.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0#h[]

I also ran across this very interesting article about the neccessity of the community in the formation of the self. Like some of the commentators below I too have reservations about the kind of family history that children grow up with when they learn under the grip of trauma and negativity. But I do strongly believe that we find ourselves only through storytelling, and not just within families either. We draw ourselves from a wider world of logic and literature. Who am I to my mother and my father, to the centuries that precede me, and the centuries that will continue without me? What are villains and heroes, what is suffering, what is determination, what have others done so that I too may do if I must? What is love, that I may love? Whole tropes of behaviour and paths to choose from, to deny or adapt and learn from, all from the simple and fundamental act of conversation: of interpretation and interaction, of eschatologies, of narrative.

For here too are the tropes of tragedy.

SALARINO

Why, I am sure, if he forfeit, thou wilt not take

his flesh: what's that good for?

SHYLOCK

To bait fish withal: if it will feed nothing else,

it will feed my revenge. He hath disgraced me, and

hindered me half a million; laughed at my losses,

mocked at my gains, scorned my nation, thwarted my

bargains, cooled my friends, heated mine

enemies; and what's his reason? I am a Jew. Hath

not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die? and if you wrong us, shall we not

revenge? If we are like you in the rest, we will

resemble you in that. If a Jew wrong a Christian,

what is his humility? Revenge. If a Christian

wrong a Jew, what should his sufferance be by

Christian example? Why, revenge. The villany

you teach me, I will execute, and it shall go hard but I

will better the instruction.

-- The Merchant of Venice, Act 3, Scene I

Fierce, flagrant, incorrigibly biased, by God, and though it certainly doesn't place Shylock anywhere near a moral high ground for wanting to gouge out flesh from one of his erstwhile bullies, and legally too, he makes me recognise in myself what drives it. I spent three quarters of the play rooting for Shylock out of pure gut feeling. Later I realised that it was because he stood for the impotent rage of the oppressed. I never want to be his position and I certainly never want to be like him, but I think this rage is something that everyone can understand, and it makes the question of permissibility even knottier and more difficult. Every character in a narrative, conversational or written or visual or otherwise, is a foil and a mirror to the reader's own.

We are learning every day. In reference to the picture article above, I do actually think the world owes me a living. If I didn't, I'd be dead. But the way I see it, the world has offered up to me all the living that I could have wished, suffering and love and wealth and shame together, and what I owe it is what I owe it in return. What I owe is that which I make of my life and the abolishment of all that fails to support life. And my strength is the strength that others can lean on.

Sunday, March 10, 2013

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Had I the heavens' embroidered cloths,

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

Enwrought with golden and silver light,

The blue and the dim and the dark cloths

Of night and light and the half-light,

I would spread the cloths under your feet:

But I, being poor, have only my dreams;

I have spread my dreams under your feet;

Tread softly because you tread on my dreams.

-W.B. Yeats, 'He Wishes For The Cloths of Heaven'

One day I will do a piece of beautiful artwork embroidered around a hand-calligraphed rendition of this poem as a gift to myself and a reminder of what I must do for my students. But that will be for when I have time.

Sunday, March 3, 2013

Words, words, words

O for a muse of fire, that would ascend

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars; and at his heels,

Leash'd in like hounds, should famine, sword and fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, and gentles all,

The flat unraised spirits that have dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object: can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O, pardon! since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million;

And let us, ciphers to this accompt,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high upreared and abutting fronts

The perilous narrow ocean parts asunder:

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts;

Into a thousand parts divide on man,

And make imaginary puissance;

Think when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i' the receiving earth;

For 'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there; jumping o'er times,

Turning the accomplishment of many years

Into an hour-glass: for the which supply,

Admit me Chorus to this history;

Who prologue-like your humble patience pray,

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play.

As of now there is a debate on the dangerously low volume of Singaporean students who choose to take Literature at the 'O'-levels. I have many ideas of my own but such similar sentiments have been articulated so well by others -- friends, colleagues, scholars, writers -- that there is very little left for me to say. In the prologue to Henry V, the audience is asked to ride the line of ambiguity that is the suspension of disbelief, and so doing conspire with the play to create worlds. Literature, the study of words, applies the critical spirit to this suspension of belief, and if correctly done it is the means by which this abstract new world ruptures into a painful awareness of one's own. It means to read the insidious craft of the wordsmith and reveal its unresolvable human preoccupations. Technical to the last, it binds deeply to the instinct of the reader, and challenges him to respond intelligently -- and honourably. It prioritises the voice and the story; it creates an awareness of historical identity. Text and life, each reflecting and illuminating the other, engender with these mere words a dangerous playground of questions, forcing the mind outwards at last into feeling the webwork of prejudices that have shaped them into who they are.

These are some reasons for why I see value in Literature. They are not, as one might say, safely 'vocational'. Neither are my sentiments 'pragmatic', not in the commercial sense of the word. But surely there must be some value in training children to see the world as the facet-ridden, equivocal place that it is, and furthermore to critically navigate the mazes of words that they will encounter even in areas as 'pragmatic' as politics and journalism. And, just as surely, to acknowledge how the vestiges of minds long dead remain in cultural consciousness because they professed vital truths on the vexed issue of living. In the words of Jeanette Winterson,

'To the bean counters and economic gurus, a poem looks like the most useless thing on earth. It is not a money machine, you can't sell it to Hollywood or use it for product placement. You can't say long it will take to make, or how long it will last, (how maddening in an economy that depends on throwaways, that a poem can last forever). The poem, by its very nature, questions the dominant values of our world, and as William Carlos Williams put it, 'it is hard to get the news from poems/ but men die miserably every day/ for lack of what is found there.''

The brightest heaven of invention,

A kingdom for a stage, princes to act

And monarchs to behold the swelling scene!

Then should the warlike Harry, like himself,

Assume the port of Mars; and at his heels,

Leash'd in like hounds, should famine, sword and fire

Crouch for employment. But pardon, and gentles all,

The flat unraised spirits that have dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object: can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France? or may we cram

Within this wooden O the very casques

That did affright the air at Agincourt?

O, pardon! since a crooked figure may

Attest in little place a million;

And let us, ciphers to this accompt,

On your imaginary forces work.

Suppose within the girdle of these walls

Are now confined two mighty monarchies,

Whose high upreared and abutting fronts

The perilous narrow ocean parts asunder:

Piece out our imperfections with your thoughts;

Into a thousand parts divide on man,

And make imaginary puissance;

Think when we talk of horses, that you see them

Printing their proud hoofs i' the receiving earth;

For 'tis your thoughts that now must deck our kings,

Carry them here and there; jumping o'er times,

Turning the accomplishment of many years

Into an hour-glass: for the which supply,

Admit me Chorus to this history;

Who prologue-like your humble patience pray,

Gently to hear, kindly to judge, our play.

Henry V, William Shakespeare

As of now there is a debate on the dangerously low volume of Singaporean students who choose to take Literature at the 'O'-levels. I have many ideas of my own but such similar sentiments have been articulated so well by others -- friends, colleagues, scholars, writers -- that there is very little left for me to say. In the prologue to Henry V, the audience is asked to ride the line of ambiguity that is the suspension of disbelief, and so doing conspire with the play to create worlds. Literature, the study of words, applies the critical spirit to this suspension of belief, and if correctly done it is the means by which this abstract new world ruptures into a painful awareness of one's own. It means to read the insidious craft of the wordsmith and reveal its unresolvable human preoccupations. Technical to the last, it binds deeply to the instinct of the reader, and challenges him to respond intelligently -- and honourably. It prioritises the voice and the story; it creates an awareness of historical identity. Text and life, each reflecting and illuminating the other, engender with these mere words a dangerous playground of questions, forcing the mind outwards at last into feeling the webwork of prejudices that have shaped them into who they are.

These are some reasons for why I see value in Literature. They are not, as one might say, safely 'vocational'. Neither are my sentiments 'pragmatic', not in the commercial sense of the word. But surely there must be some value in training children to see the world as the facet-ridden, equivocal place that it is, and furthermore to critically navigate the mazes of words that they will encounter even in areas as 'pragmatic' as politics and journalism. And, just as surely, to acknowledge how the vestiges of minds long dead remain in cultural consciousness because they professed vital truths on the vexed issue of living. In the words of Jeanette Winterson,

'To the bean counters and economic gurus, a poem looks like the most useless thing on earth. It is not a money machine, you can't sell it to Hollywood or use it for product placement. You can't say long it will take to make, or how long it will last, (how maddening in an economy that depends on throwaways, that a poem can last forever). The poem, by its very nature, questions the dominant values of our world, and as William Carlos Williams put it, 'it is hard to get the news from poems/ but men die miserably every day/ for lack of what is found there.''

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)